The Tower

A restoration filled with history and charm

The almost thousand-year history of this incredible building emerges from the inscriptions, coats of arms and mysterious symbols left by its ancient inhabitants.

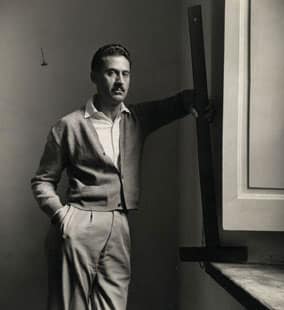

But also from furniture, a piece of European design history and Italian art. Emilio Jesi, the man who restored the Tower in the late 1960s, was a great collector of paintings and sculptures and a lover of Italian and European design. He called a famous architect, Franco Albini, who left his modern and elegant mark that we, the last heirs, try to complete with respect for memory and the present time.

Architecture

Twenty-eight meters high and divided into five floors, the Tower is a construction with a quadrangular escarpment base made of selagite: the lower part has a two-tone pattern obtained with alternating rows of light and dark stone.

The walls vary in thickness from over three meters at the base to about two meters at the highest part. Among the slits located on the sides, all arched and arranged asymmetrically, of particular interest are the two oculi strategically facing one toward the Volterra Fortress and the other toward the Sillana Fortress.

History

The Tower of Montecatini was built in the first half of the 14th century at the behest of the Belforti family of Volterra, who entrusted its construction to the stone master Ghetto da Buriano. Various clues suggest that an earlier version of the tower, probably smaller in size, was already present in the 11th century, there where the present one stands. In fact, the tower is thought to have been part of a larger fortification effort as early as the 11th century that included a city wall and several smaller towers. The work of the Belforti family in Montecatini is inscribed in the rise to power of this family, which, after a long dispute with the rival Allegretti family, conquered the seigniory of Volterra in 1340. However, the parable of the dynasty ended very soon: in 1361 Bocchino Belforti lost the support of Florence and was hanged by the Volterrani on charges of betraying the city by selling it to the Pisans for 32,000 florins. The Belforti were driven out of Volterra, which fell, amidst ups and downs, under Florentine control. The same fate befell the Montecatini Tower.

In later centuries the tower was the seat of captains sent by the Communes of Volterra and Florence, and belonged to the Pannocchieschi, Inghirami and Rochefort families.

In the 1700s it was described as seriously damaged by lightning and the wear and tear of time.

During World War II, it was used by Montecatinesi as a shelter during bombing raids, was hit by cannons on several occasions, and was further damaged. Despite everything, the structure has always remained solid. The village elders tell that, until the restoration, it was always possible, though risky, to get to the top.

Restoration

In the late 1960s, the Tower was purchased by Emilio Jesi, a coffee industrialist and owner of the company of the same name, Caffè Jesi, established in Milan in 1848. Passionate about contemporary art, Emilio Jesi was a great patron, and his collection is still housed in the Brera picture gallery in Milan.

Jesi was fascinated by the idea of restoring such an ancient asset, of carrying out a work of public interest that the Italian state seemed unable to complete. An admirer of Franco Albini's rationalist architecture and a design enthusiast, Jesi entrusted the famous architect and designer to direct the work. It was necessary to reopen a stone quarry and hire a team of stonemasons.

The restoration brought no major changes to either the exterior or interior. But Albini's hand is clearly visible in the furnishings: a sober, solemn style with simple elements typical of industrial architecture mixed with pieces of the best Italian and European design.

Highlights include Albini's own "Margherita" armchair, a work exhibited in the world's leading design museums, Castiglioni's "Gatto" lamps, Tobias Scarpa's "Fantasma," Alvaar Alto's "l'Ala d'Angelo," and Gino Sarfatti's "1094." Then there are McGuire's director's chairs and armchairs, Tapio Wirkkala's leaf tray, and fine pieces of craftsmanship such as the very light chiavarine chairs or Thonet's coat rack.

The Tower was conceived as a temple of beauty, and according to this spirit it has been preserved over the years. In the summer of 2012, the bathrooms were renovated: architect Spartaco Paris, a professor of Architectural Technology at Bari Polytechnic, designed the project along Albini's lines, updating the facilities according to changing comfort needs: the showers were modernized, and more space was gained through careful arrangement of the elements. The second major work was done on the electrical system to bring it up to modern safety standards and to allow every room to be reached by a wireless satellite Internet connection. The latest intervention is in 2020, signed this time by architect Antonella Rossetti, aimed at rationalizing the spaces, making the rooms independent from the passage to the terrace, and refreshing and renovating the rooms.